The Signal Dance of the Honey Bee

History of discoveries

It was known long ago that the honey bees were able to attract their nestmates to a new rich source of food found by any of them in the field or in the wood. Remarkably, they do not simply stimulate nestmates to fly out, but recruit them to reach the definite site. Spitzner (1768), Unhoch (1823), Vitvitskiy (1843) described how a forager bee on her return to the hive runs about circles (dances) among other bees; some of these authors guessed about the role of the dance in the recruitment.

The great investigator of honey bee behaviour, Karl Ritter von Frisch (born in Vienna in 1886, worked in Munich since 1910, died in 1982) found out, that the forager dancing on the comb either enscribes a simple circle, alternating direction of rotation from round to round, or sways to the sides (waggles) at some sector of the circular run. At that time, the difference in dance figures was ascribed to the difference in food quality. Later on (1946, 1950), v. Frisch created the challenging hypothesis: the dance outline indicates the site of the food source, the rate of the dance depends on the distance, and direction of the waggling run of the dance - at the vertical comb - corresponds to direction of flight with respect to the solar azimuth. Von Frisch even proposed to his trustless colleagues to measure the dance direction and dance rate with the aid of a protractor and a stop watch by themselves and afterwards to follow this bee’s advice and to find a small cup with the sirup in the field or among the orchard. Then wait until the marked bee returned to this cup. The bees signal by their dance location of the food source as well as possible nest location suitable for a new swarm.

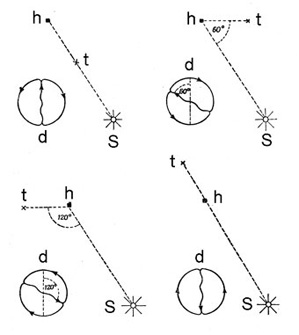

|

|

| Scheme of targeting in the dance of the scout bee. (d) outline of the dance, (h) hive, (S) Sun, (t) trough. |

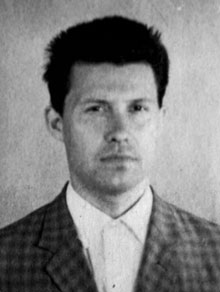

Karl von Frisch |

Discoveries of Karl von Frisch on the colour vision of honey bees, their taste and olfaction, their ability to navigate by the polarized skylight (ability lacking in a man), their astonishing signal language have been awarded with the Prix Nobel in medicine or physiology in 1973, together with two other notorious investigators of animal behaviour: Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen. Karl v. Frisch continued his studies on honey bee sensory physiology with assistance of his student, Martin Lindauer.

|

Martin Lindauer (left) and Harald Esch. |

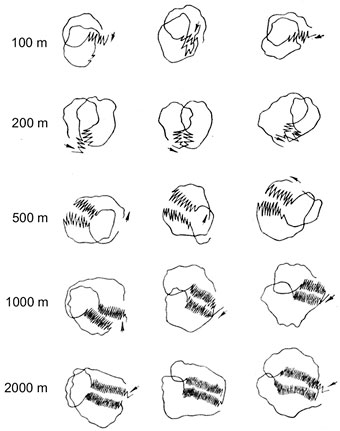

The waggling run is the most informative part of the orientation signal. Von Frisch measured its direction with the aid of a simple protractor with a plumb arrow. The number of lateral body oscillations was evaluated for the first time by Harald Esch (1956) and Wolfgang Stehe (1957) with the aid of electromagnetic recording; Karl von Frisch and Rudolf Jander counted oscillations visually, watching a film of a dancing bee at a slower frame rate. Oscillation frequency was in the range 12-18 per second. Precise frame by frame reconstruction of movements of the dancer and following bees was firstly accomplished by Ivan Levchenko (1961) in Ukraine. (Ivan Levchenko was born in 1930, began his investigations in Kanev and continued in Kiev: in the Schmalhausen-Institute of Zoology (National Academy of Sciences) and in the Prokopovich-Institute of Beekeeping (Ukrainian Academy of Agricultural Sciences), died in 2012). Levchenko projected a film on a paper sheet and traced position of some bright mark at the bee’s abdomen frame by frame. Cinegrams provided detailed description of the dance figures, precise count of lateral oscillations, dependence of this count upon flight distance, race of the bee, strength of the colony and other factors.

|

|

| Cinegrams of signal dances of honey bees. The farther is a trough, the longer is the waggling part of the dance. | Ivan Levchenko |

The number of oscillations per one dance round is directly proportional to the flight distance. Bees of the Steppe Ukrainian race add one extra oscillation per 60 m of the distance increment. Respectively, duration of the waggling run increases as well as the total duration of one dance round, while the dance rate (number of rounds per minute) slows down.

The story on the signal language of honey bees was narrated in the full-size film “The Animal Language” (Kiev Studio of Popular Scientific Films: screenwriter Yuri Alikov, producer Felix Sobolev, cameraman Leonid Pryadkin, 1967). This film was awarded with the USSR State Prize in Arts; it was demonstrated in many countries. Scenes with bees were arranged by Ivan Levchenko and his colleagues.

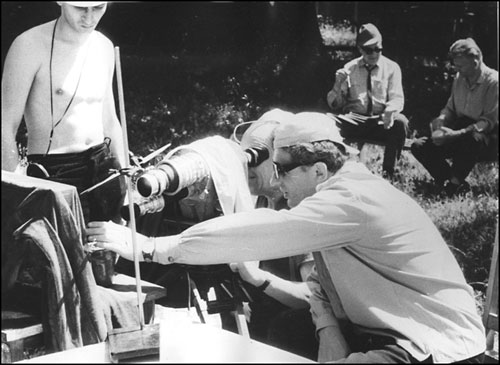

|

Filming of a hive for the movie «The Animal Language » at the experimental

center «Teremki» (Institute of Zoology). The producer Felix Sobolev — in the foreground, the cameraman Leonid Pryadkin is filming. |

Physiology of behaviour and signalization in honey bees was investigated also in the Pavlov-Institute of Physiology, USSR Acad. Sci., recently Russ. Acad. Sci. in Koltushi, near Leningrad (M. E. Lobashov, N. G. Lopatina, I. A. Nikitina, E. G. Chesnokova).

|

Ivan Levchenko records the signal sounds of honey bees in a hive placed among a lake (the Black Sea Reserve). |

The signal dance is accompanied by the peculiar stridulating sound, very unlike to abrupt or long buzz of worker bees and queens on the comb. H. Esch was the pioneer in discovery of this quiet stridulation, firstly as a bee’s body vibration revealed by electromagnetic means (1961), later he wrote it via a microphone on a tape-recorder and further on an oscillograph. I. Levchenko demonstrated by synchronous filming and sound recording of the dancer that the bee emits the sound only during the waggling run. The continuous oscillographic recording from a microphone on the running film provided precise measurement of frequency and duration of oscillations upon various experimental conditions. How does a bee stridulate?

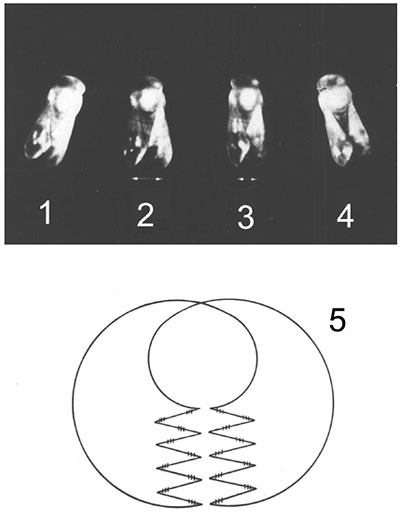

I. Levchenko and his colleagues (Bodryagin, Levchenko, Frantsevich and Shalimov, 1966) filmed bees with a high rate camera (750 frames per second), but watched them at 24 frames per second. Dashing movements are seen now as slow and fluent, in tiny details. During the waggling run, a bee sways from side to side, proceeding with short steps. The wings of the dancer are not folded together all the time long: the bee flaps her wings periodically in short series twice per one oscillation cycle. These flaps are of reduced amplitude, but clearly noticeable in the slow frame flow. Each series contains 2-6 flaps. The flaps of adducted wings produce the stridulating sound, each flap corresponds to one sound pulse in a series, all series fuse in a trill.

|

High rate filming of a dancing scout bee. (1-4) Frame by frame images of the bee during one-side sway. The glitter of the wings and their position relative to the body change during wing vibrations. (5) Sceme of the waggling dance. Small dashes indicate time of wing vibrations during sways. |

Wings are actuated by powerful wing muscles in the thorax, however, during the dance wings are not straddled sideward, in contrary to the flight. That is why the whole body of the bee vibrates in pace with the muscle contractions. Vibration is transmitted to the whole comb. Mute dances do not attract follower bees, as it was demonstrated by H. Esch.

Information on the direction and distance of the flight to the food source is encoded in rounds of the dance, in stridulations, in comb vibrations. Moreover, the dancer stops from time to time and rewards one of the followers with a drop of nectar. Thus the odour and quality of the food are reported to other bees. Whether the followers understand any of these signals?

Despite the convincing fact that the dance of the forager contains rich information - for a human observer, - some scientists could not believe during decades, that other bees, these small creatures with tiny brains, could understand the targeting signal. Is it possible to transmit the signal without the real dancing forager? Stehe (1957) introduced a vibrating bar of a bee size among the bees on a comb. Even such a simple model attracted surrounding bees.

Ability to understand the dance signal was most convincingly demonstrated in experiments with substitution of a live bee with a mini-robot which simulated in details the dance figure, waggling, sound, and food reward. This robot was designed and elaborated during several years by the Danish scientist Axel Michelsen (1989, 1993). The bar of a bee size was suspended on an arm, driven along the necessary trajectory by a computer program; the bar possessed a container with the sirup and a mini loudspeaker inside. The robot surfed above the comb among other bees. It was supposed that recruits would fly to the certain feeder in accordance with the robot’s targeting, while check feeders at some distance from the target would stay abandoned. And it was really so: recruits properly found the target.

|

Axel Michelsen |

How do other bees perceive movements of the dancing bee inside the dark hive? A bee is able to do this with the aid of her organs sensitive to the touch, sound, substrate vibration. The surface of the bee’s body is covered with hairs sensitive to the touch, but antennae of the bee are most sensitive. The antenna encloses a special organ sensitive to airborn sounds. Subgenual mechanoreceptors in the tibiae are especially sensitive to substrate vibrations. We acknowledge great contribution of German scientists: Hans-Joachim Autrum, Martin Lindauer, Jurgen Tautz - to studies of these sensory organs.

|

| The suite of worker bees surrounds the signalling scout bee

with pollen pellets. Selected still frames from a movie. |

Ivan Levchenko was the first who paid the serious attention to behaviour of bees following the dancer. Tracing film records, he (together with his colleagues) demonstrated how the hive bees are attracted to the dancer, follow her and leave her since some time (1966, 1967, 1969). Importantly, the dancer alternates direction of the round run (clockwise or anticlockwise) from one round to the next one, while direction of the waggle run is always constant. Therefore the followers in serial rounds get to the right side or to the left side of the dancer; after several rounds their average position is behind the dancer. Such an averaging simplifies solution of the complicated orientation problem: given own position on the comb with respect to gravity, location of touch to the dancer with respect to the own body, and, may be, direction of movement of the waggling dancer by the follower, one must compute dancer’s direction of the waggling run with respect to gravity.

Bees at different sides of the dancer obtain different touch signals with their antennae. This fact was discovered by Ivan Shalimov (1967), the Levchenko’s student, from analysis of cine records of antennal movements in the followers: a bee staying at the side of the dancer feels both her antennae compressed to the head or released in synchrony, while both antennae in a bee behind the dancer obtain antiphasic strikes: one inward, other outward.

|

Ivan Levchenko |

|

|

|

| Ivan Shalimov | Leonid Frantsevich | Veniamin Bodryagin |

60 years elapsed since pioneer discoveries of K. v. Frisch. Active studies of signalization in honey bees are continued by Jurgen Tautz and Wolfgang Kirchner in Germany, by Fred Dyer in USA. There is impossible to tale in our brief story, how the bees measure distance of their flight, find direction by the Sun and blue sky, correct for the visible movement of the Sun across the sky, learn and recognize position of the hive entry or the feeder among the visible surround, discern colours and odours of flowers and put scent marks by themselves.

|

Jurgen Tautz |

Read the books about bees and watch the bees attentively by yourselves. Learn the Bee’s Language !

Title :: Signal Dance :: Signal Sounds :: References